3 Simple Spelling Strategies for Reading Unfamiliar Words

“E-V-A-P-O-R-A-T-I-O-N” spelled a 4th grade student. She spelled this word because she wasn’t sure how to pronounce it. Huh? Yeah. Spelling helps her make sense when she’s reading unfamiliar words.

Attending to each letter in the word enabled her to process the spelling and then pronounce the word. She adjusted the pronunciation of the first < a > from /eɪ/ (ā) to /æ/ (ă) as she worked it out.

Pronunciations are phonetic and subject to individual articulations that vary by person, region, culture, dialect. Sound dissipates. It doesn’t last. Accurately discerning the phonemes in a spoken word does not come naturally or easily for dyslexic students. It’s usually their weakest skill.

Many of my dyslexic students have had great success using strategies that don’t require them to focus on their weakness.

Spell it. Read it.

“Both Asian and African elephants have very long trunks.” That’s the text.

A 3rd grade student read: “Both Asian and African elephants have very long tusks.”

Both trunks and tusks are bound to come up when you’re reading about elephants.

She continued reading, not noticing the error since it worked syntactically. Later, we looked at the sentence again. She reread it saying “tusks.” As soon as she spelled it aloud, she said, ‘trunks.’

1. Spell it out.

So simple and so effective. Very often this is all it takes for a student to figure out the previously unfamiliar word. Sounding out works some of the time, but spelling out works more consistently.

In a tutoring session, students usually spell out loud, but they use it silently in their classrooms too.

As students learn about consonant and vowel digraphs, they spell those literal units together quickly as if they were one letter.

Recognizing digraphs & trigraphs improves their processing that < ea > could be spelling /i/, /ɛ/, /eɪ/ (ē, ĕ, ā) or schwa rather than thinking through <e-a>. We are always working to build automaticity and independence.

2. Check the Structure—(prefix + base + suffix).

“Mosquitoes and flies swarm busily, seeking for their next snack.”

A 5th grade student pronounced ‘busily’ as “buzzily”. She knows <s> can spell /s/ or /z/. She spelled it, but she didn’t yet recognize the word. Next, we check the word’s structure, looking for affixes (prefixes & suffixes) and predict what the base element could be in the word. Sometimes it’s obvious and sometimes it’s not.

She noted the <-ly> suffix. No prefixes. So, how is the base spelled?

<b-u-s-i>

She knows that English words do not end in < i >, and she knows the suffixing convention for words ending in <y>. Finding the base element gave her what she needed.

(The suffixing convention for words with a final <y> is that we change those to an <i> unless that would cause <ii> or the final <y> is part of a vowel digraph or it’s part of a compound word like ‘anyone’ or ‘busybody’. Other than those 3 circumstances, we change <y> to <i>.)

Once she looked at the morphemes, she recognized ‘busy’ in <busi>.

Prefixes and suffixes are a recurring feature of English and because they are so regular in their appearance, they become a memorable pattern. Helping students use those patterns to recognize or discover an unfamiliar word gives them a tool they can apply independently. We know memorizing lists of words works (it lasts, sticks to our memory) for some people. For others, it feels like it evaporates. These people may find word structure very useful for unfamiliar words.

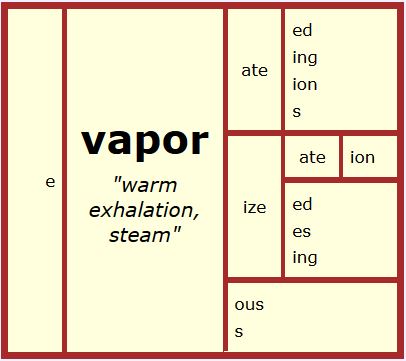

Once they are introduced to this strategy, it doesn’t take long for students to notice them on their own. Look at the recurring suffixes in this matrix.

3. Consider the Phonemes

A 3rd grade student: “He went under the /fɛnk/ ‘fĕnk’ and into the yard.”

The sentence: “He went under the fence and into the yard.”

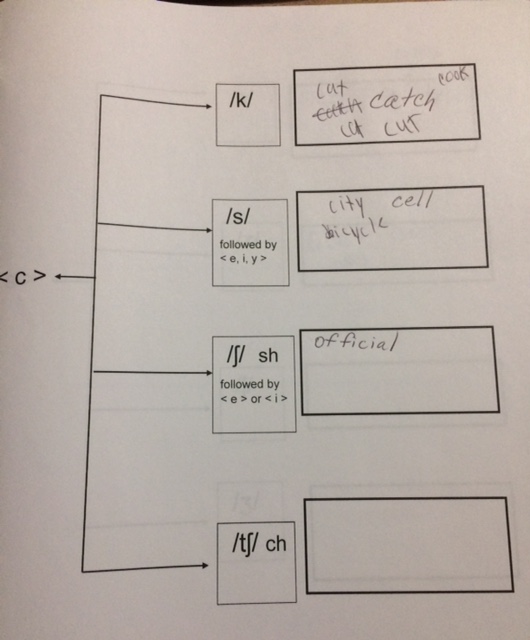

Even though this student had worked with spelling of <c> followed by <e> pronounced /s/, it was not transferring to his own use; it was not his yet.

Strategy 1-He spelled it aloud “f-e-n-c-e” and said /fɛnk/.

Strategy 2-No prefixes or suffixes.

“Besides /k/, what phonemes can <c> spell?” I prompted.

A quick look at his phoneme chart for <c> might give a clue.

I could ask, “What job is the final <e> doing in this word?”

His noticing this for himself will mean more and hopefully stick with him longer than if I’m just telling him the answer.

Considering the other phonemes for a spelling helps students move past the default grapheme-phoneme correspondences they sometimes get stuck on. They need this skill to make sense of words when <t> isn’t spelling /t/ but it’s spelling /ʃ/ (sh) as in ‘action’ or it’s spelling /tʃ/ (ch) in ‘nature’.

Ultimately, the goal is to make sense of the word in the sentence. Students learn to ask and answer this question: “Would that word make sense here?”

Quick and efficient strategies for reading unfamiliar words:

- Spell it out.

- Are there any prefixes or suffixes? So the base is …? (spell the base)

- Consider other phoneme options for a grapheme.

- Does this word make sense?