Practical Ways to Engage Dyslexic Students

(This post contains affiliate links. Read my full disclosure.)

Wherever you teach—classroom, home, or tutoring office, your goal is to help your students become literate. Sometimes students have given up on learning and themselves. Let’s talk about some practical ways to engage dyslexic students.

Since we’re playing catch-up with many of these students, our time with them must be as effective as possible. The time we spend together filling in literacy gaps must count.

We want to make learning convenient for the student. By “convenient,” I mean “doable, accessible”.

Here are some practical ways to engage dyslexic students in learning.

- Encourage Questions & Listen

- You Teach, They Teach

- Brief Focused Attention

- Play Games

Questions & Listening

Our Questions

Of course, teachers ask questions. They help you assess what students know. Other questions let you see what they can apply in common situations.

But let’s turn the tables.

Their Questions

Encourage students to ask you about surprising words they find. Trust me, this is one of the best ways to engage them in learning. Many students aren’t used to being the one asking questions. It can take time for them to be comfortable doing it. What’s the benefit of them asking you about a “crazy word”?

Consider how you engage with learning. When you want to know something, aren’t you much more likely to listen to the answer? Maybe you even ask more questions about the topic. Because you’re thinking about it.

When it’s their question, it carries more staying power. They’re more invested in finding out.

Listen to what they’re asking. What do they understand or misunderstand? It’s a great informal assessment of their current concept knowledge.

What if they don’t have a question? Ask one of your own.

Try: “I’ve wondered why there is a <w> in two.” Then use tools to find the answer together, leading the student in the search for the reason. Look it up in a dictionary and in an etymology dictionary. Find relatives. Propose your hypothesis. Maybe with an upcoming question, support the student in leading some of the investigation more independently. Who doesn’t like to be a detective?!

You Teach, They Teach

You Teach

Suppose you’re going to teach a concept like the <ai> vowel digraph’s phonemes and typical position within a word. What do you know they already know about this? Do they need a review?

Prepare the Foundation

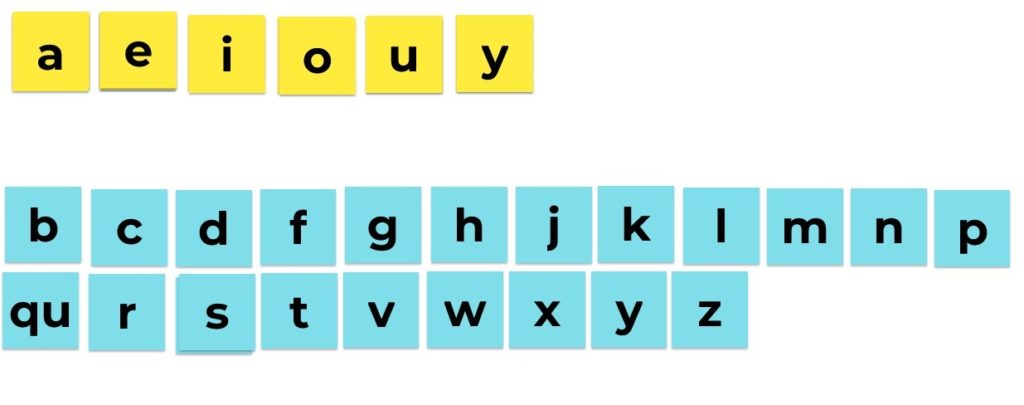

Plan how you’ll briefly explain this vowel digraph. Be prepared to explain vowels and consonants. Is your student fluent in the difference between consonants and vowels?

Some literacy gaps that middle and high school students have are surprising. Don’t assume because they’re in ____ grade that they know. Ask them which letters are vowel letters in general or specifically in a given word. Check if they know what sound a vowel is spelling in a word.

Maybe the term, “digraph,” is unfamiliar. Help them fill in the blank spots on any terms you use.

I Said, “Brief.”

When we’re teaching, brief and concise isn’t always easy to pull off. Some of us struggle with that more than others. I haven’t mastered it yet.

In Whole Brain Teaching for Challenging Kids, Biffle suggests teaching concepts in small chunks with no more than 50 words in less than 30 seconds. But this can’t be rapid-fire talking. Your rate of speech should be clear and easily digestible. Figure in students with ADHD or auditory processing disorder, and you’ll want to slow down a little more. So you’ll have significantly fewer words in your sound bite, and that’s okay.

“The more we talk, the more students we lose.”

Chris Biffle

You may lose students with auditory issues after the first 20 words, when they zoned out because it felt like overload. Be specific, simple, and slow it down.

Because in just a sec, you’re going to ask the students to teach what you just explained. It has to be brief so they can hang on to the information to share.

For example, you might say, “One way we can spell /eɪ/ (the long-A sound) is with the <ai> vowel digraph.”

They Teach

In a one-on-one tutoring situation, ask them to teach it to you. They repeat it back with support, you filling in what they missed. It’s okay if they say it a little differently.

You might use the teaching back and forth as part of an introduction to finding <ai> in a word hunt while you’re reading a book. You might use it again with a review after the student has misspelled a word. It’s very flexible. It’s useful in any subject.

Maybe your student has noticed with your help that <ai> is used at the beginning and middle of words, but you haven’t found any with <ai> spelling /eɪ/ at the end of a word.

Then you can introduce or review more information. “<AI> can spell /eɪ/ at the beginning or middle of a word, but not at the end.”

Then the student teaches it again.

If you’re at home or in a classroom, they can teach you or their classmates with you walking around listening to student teaching. Chris Biffle encourages classroom students to teach each other in pairs. If their teaching is confusing, ask questions to help them clarify and rephrase it.

It may start as parroting back the information. In time, you’ll hear them putting the information into their own words. It’s becoming theirs.

“To teach is to learn twice.”

Joseph Joubert

Teaching can be done with funny voices that students mimic when it’s their turn. Use an old grumpy voice, a minion voice, a baby voice, a sing-song voice, a slow voice, etc. We hang on to things we learned or heard with humor involved.

Here’s Their Homework

After class or your session, ask the student to teach the concept to a family member, maybe even the dog. You’ll be rewarded with a grinning student relating how they taught a mom, dad, or grandparent something they didn’t know.

Brief, Focused Attention

Online tutoring sometimes means redirecting distracted students. It’s the same in the classroom or at home. I’ve used “1, 2, 3, eyes on me”. Some teachers use a clapping attention-getter with the teacher clapping a rhythm that the students answer. Chris Briffle suggests teaching students, “hands and eyes.” When you say that, the student folds their arms and focuses their eyes on you for a brief time. Different approaches work with students, and it’s can be nice to add some variety.

Engage Dyslexic Students with Games

I’m going to tell you my favorite way to increase learning and engagement: Games! But there’s one requirement for them to truly be engaging. Whatever the game, there must be an equal chance for anyone to win. One of the most popular games with my students is Wipe Out. We use it for reading and spelling practice. It’s included in each of the three suffixing games.

All sorts of games like Bingo, Connect 4, or any roll-the-dice kind of board game can be used as concepts are reviewed and practiced. Each time they take a turn, they read a word, decide which of two words is correctly spelled, etc. When we play games, their learning mistakes are never penalized. Mistakes are when we learn.

Mistakes = Learning

When dyslexic students make mistakes, reinforce what they did right. Maybe you can see what they were thinking. Recognize their thought process. Ask questions to help them see the error. Sometimes they won’t know. Don’t make them sweat out an answer they don’t remember.

Share your mistakes. Be an example of admitting mistakes and being positive about what you’re learning from that.

Recognize their Micro-Wins

Praise what they did well while you review concepts you worked on. Elaborate on their micro-wins. Recognize when they catch their own errors, when they’re thinking through a problem, or applying what they know.

Every taste of success encourages hope for future successes.